Deconstructing Olfactory Pyramids:

Unraveling Deceptive Myths in Modern Perfumery

What are Olfactory Pyramids?

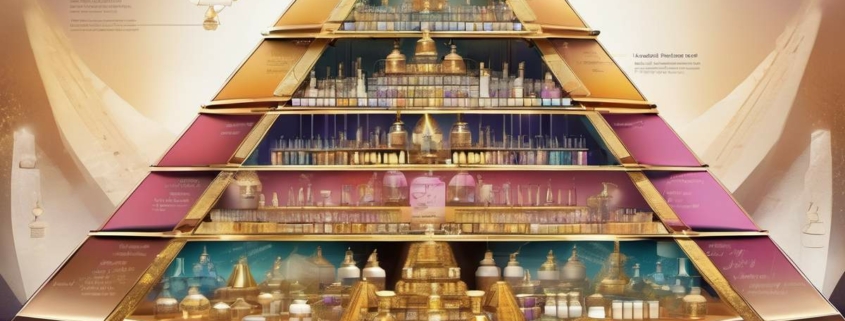

Olfactory pyramids, also known as fragrance pyramids or scent pyramids, are a graphical representation commonly used in the perfume industry to illustrate the composition and structure of a fragrance. These pyramids are intended to provide consumers with a visual guide to the various notes or ingredients present in a perfume and how they unfold over time.

The pyramid is divided into three sections, representing the top notes, middle notes (or heart notes), and base notes of a fragrance. Each section corresponds to a particular phase in the perfume’s evaporation process on the skin. Here is a breakdown of each layer:

- Top Notes: These are the initial scents you smell when applying a fragrance. They are light, volatile, and fleeting, typically lasting for the first 15–30 minutes. Common top notes include citrus, fruity, and fresh herbal elements.

- Middle Notes (Heart Notes): They are supposed to emerge after the top notes have evaporated, but in reality, they are there from the beginning and are smelled together with the top notes. They are supposed to form the main body of the fragrance, but a body is made of bones, flesh, and skin (top, middle, and base notes). You can’t say that flesh is the main body. They are supposed to last for a few hours.

- Base Notes: These are the final notes that become noticeable after the top and middle notes have dissipated, but this happens only in chemical perfumes. In a natural one, none of the ingredients dissipate completely. Base notes are longer-lasting.

The pyramid shape is supposed to convey visually how a perfume’s scent evolves over time, with different notes dominating during each phase. However, the pyramid is a simplification and the actual experience of a fragrance is much more complex. Pyramids would be totally inadequate to explain a natural perfume, as most of the natural ingredients overlap between these layers.

In the realm of perfumery, the concept of olfactory pyramids has long been considered a guiding light for fragrance enthusiasts. However, if you think these pyramids genuinely provide insights into a perfume’s ingredients or its scent, it might be time to reassess. In reality, olfactory pyramids are nothing more than a marketing tool, strategically employed to entice consumers into purchasing industrial fragrances.

The allure of olfactory pyramids lies in their ability to transport you to an idealized world where perfumes are crafted with genuine musk, authentic amber, and real rose. Unfortunately, this dream is far from reality. The ingredients listed in these pyramids don’t correspond to what is actually present in the fragrance. For instance, if a label reads “Lavender,” it doesn’t guarantee the use of lavender essential oil but is most probably a synthetic “lavender note” reminiscent of dishwashing soap.

Olfactory pyramids typically categorize scents into three layers: top notes, middle notes, and base notes. However, this oversimplified classification fails to capture the complexity of natural essences, most of which overlap across multiple layers in terms of intensity and longevity. Rose essence, for example, is both a top and middle note, while tobacco, a potent middle and base note, demands careful dosage. The challenging nature of essences like angelica further complicates matters, as they can simultaneously contribute to the top, middle, and base notes, leaving a lasting imprint on the entire perfume.

Crucially, olfactory pyramids offer little insight into the actual perfume. This is primarily because the listed ingredients are not necessarily present in the fragrance, and even if they were, they rarely adhere to the pyramid’s hierarchical structure. The power of suggestion embedded in these pyramids can even trick your mind into detecting ingredients that are not present. — a phenomenon that has some reviewers, influenced by made-up expectations; say they smell notes that are purely products of their mind.

To illustrate the influence of suggestion, consider an experiment conducted by Avery Gilbert. Spraying nothing more than water into the air, he warned the audience about a potentially harmful smell, planting seeds of apprehension and distrust. He did that, insisting that the smell was not harmful at all and that the audience should not worry. As a result, some individuals reported perceiving a foul odor and even experienced nausea, prompting them to exit the room. The catch? It was just water. This experiment underscores the significant role our brains play in the olfactory experience, emphasizing that we often smell more with our minds than our noses.

In conclusion, the next time you encounter an olfactory pyramid, approach it with a healthy dose of skepticism. What you read on the label is very unlikely to be true in any measure, and the reviews you read about the fragrance should be taken with a grain of salt. If you try your hands at perfume-making, do not think to reproduce a commercial perfume for a customer following the pyramid. You will end up with something completely different.

As I always repeat to my students, “Making perfumes is easy, selling them is difficult”.

If you make natural perfumes, you may avail yourself of pyramids as a tool of communication with your customers, in order to sell your fragrances more easily. Your perfume pyramid will be useful to them, but only if it truthfully informs them about the ingredients that compose your fragrance. (see Eclip list)

The pyramids of mass perfumes are only a tool of deceit, whose purpose is to sell crap as if it was fine perfumery. You may use them to convey an image of the smell, even though they are not perfectly adequate.

Unraveling Deceptive Myths in Modern Perfumery